Divided thematically into seven sections, the exhibition's focus ranges from factual analysis to prophecies, speculation, and undisguised delight in man's downfall. The result is a rollercoaster ride along the fault lines between nature and culture, human life and the universe. Visitors are forced to confront their own beliefs and experiences, and leave reassured and disconcerted in equal measure.

«Apocalypse – End Without End» was developed in collaboration with Heller Enterprises, Zurich, with scenography by Holzer Kobler Architekturen, Zurich.

The seven rooms: a walk round the exhibition

For visitors who don't take the lift, the exhibition is accessed via a temporary staircase from the ground floor to the third floor. On the way up, they encounter works by some of the artists involved in the exhibition, while humorous, macabre and fundamentalist film sequences from popular internet videos provide a taste of what lies ahead.

The exhibition itself starts by presenting the only definitive end currently foreseeable, the one apocalypse scenario which is certain to occur. In around two billion years it will be so hot on Earth that all life will cease to exist, and in four and a half billion years the sun will swell into a Red Giant and burn out. This particular fate is evoked by a dramatic light installation created by the Berlin-based media agency TheGreenEyl which visually transforms the room more powerfully than any words.

The second room explores the omnipresence of the Apocalypse - in our beliefs, prophecies and hopes, in media and religion. A goggling array of images and audio documents awaits, including a montage of End Time-related texts read out over five loudspeakers, the Last Judgement-depicting tympanum from the portal of Bern Cathedral, a theatrical production of the Apocalypse of St. John, and a Hollywood jaunt through almost forty apocalyptic films. These visions of the End Time only rarely envisage a definitive end: the eradication of evil and the rooting out of sinners is usually followed by a new and better age. The sculpture "Souvenir from Hell" by Jake and Dinos Chapman, a work of video art by Roberto Fassone and a real-time media installation by Marc Lee lend a delicious touch of irony.

The iconic image of the Blue Planet, taken from space, is a breathtakingly effective ambassador when it comes to Earth's vulnerability. This room, then, is about real dangers: cosmic catastrophes and terrestrial terrors such as meteorites and volcanoes. A work by Roman Signer sees the Wörlitz Volcano erupt. The threat from outer space is symbolized by a window from Chelyabinsk in Russia, where four years ago the best-documented meteorite shower in history took place. The greatest threat to mankind, however, remains man himself. The Danish art collective Superflex recreates the Great Flood in a branch of McDonalds, providing a metaphor for the way we are killing ourselves by consumption. Julian Charrière's film of the Bikini Atoll, the site of a series of nuclear bomb tests in the 1950s, does important work in calling to mind what we would rather forget. Other traces of human influence on the planet are symbolized by two particularly striking objects: Andreas Greiner's two-metre high 3D-printed carcass of an industry-fattened broiler (chicken bones betray the presence of humans all over the world), and an ice core from Greenland which only sophisticated technology makes it possible to display at all. Investigations of polar ice layers show that the carbon dioxide content has risen more sharply in the last decade than in the preceding 800 000 years. Photographs by Armin Linke, and Ingo Günther's globes also speak of changes that are only apparent close up.

Natural disasters have caused at least five mass extinction events in the history of the Earth, and it is likely that we are currently experiencing the sixth, this time triggered by human influence. Among the countless victims is the woodchat shrike, which just ten years ago was a common breeding bird in Swiss gardens. Thousands of species disappear globally every year – Joël Sartore's portraits lend them dignity and a face. Even the remaining fish, amphibian, bird and mammal populations are declining drastically - numbers have halved since the 1970s. An animated film projected across a whole wall explores the processes by which species emerge and disappear over millions of years, while a number of silent witnesses, mainly fossils, look on. But people die too under catastrophic conditions, and have done since they began to inhabit the planet. Their cities flourish and decline, as Camille Henrot shows in a fictitious display. Katie Paterson's celestial map charts all the stars that have already disappeared.

The constant threats that we face spark not just fear but feed defiance, denial and, in some cases, creativity. "Davon geht die Welt nicht unter" ("This is not the end of the world") sings Zarah Leander, amidst a hall full of Nazi officers swaying in time to the music. The prospect that the end is nigh inspires visions, madness, music, escape plans, rescue schemes - and, as shown by the luxury bunkers available for purchase to Americans attempting to flee the Apocalypse, there's money to be made from it too. Preparing for a catastrophe can lend meaning to life, as the vibrant "prepper" movement proves. The animal world, too, is wired to react to changes in living conditions, inspiring the designer Kathryn Fleming to create three experimental new animal species whose adaptations equip them for the world of the future. And then there's the world outside the world, often imagined in films but now perhaps more real than we thought: NASA is already holding architecture competitions for the design of Martian habitats.

Many people have experienced "their" world come crashing down. The end of the world can take on significantly less drastic forms than the end of all life or the end of the planet. Dementia patients lose their hold on reality; heartbreak can shatter an existence - the objects from the Museum of Broken Relationships are the debris of such catastrophes. Existential uncertainty abounds in this room, in sobering reports about the state of the deep sea and attempts to pollinate plants using drones, in dystopias and longings and in the illusion of victory which Elodie Pong blasts with an avalanche. Batoul Shimi's world vessels silently demonstrate the pressure they're under, while Gino de Dominicis' attempts to take flight are touching in their futile persistence. A few steps further on, Bazon Brock invites us to pause for philosophy, advising that apocalyptic thinking is a prerequisite for purposeful action.

The world hasn't ended yet - the end remains open. And so, rather than culminating in a conclusion, the exhibition finishes with a changing series of perspectives provided over time by different artists. The rules of the game are simple: the Museum invites an artist to create content for the last room of the exhibition and thus to draw their own personal line under it. The artist's contribution is displayed for a year, meaning that the final comment on "Apocalypse", the statement made from the vantage point of the end, will change over time. To emphasize this, the display will actually be changed in front of the public during exhibition opening hours. The installation Fist Teeth Money by Beni Bischof opened this series with a spectacular mix of the most diverse realities of life and media. After Bischof, the artist duo huber.huber created the last room of the exhibition with an installation. "Hello Darkness, my old friend", opened on 20 December 2018 for one year. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Christina Agapakis, and Sissel Tolaas then reconstructed the smell of an extinct plant as part of "Resurrecting the Sublime."

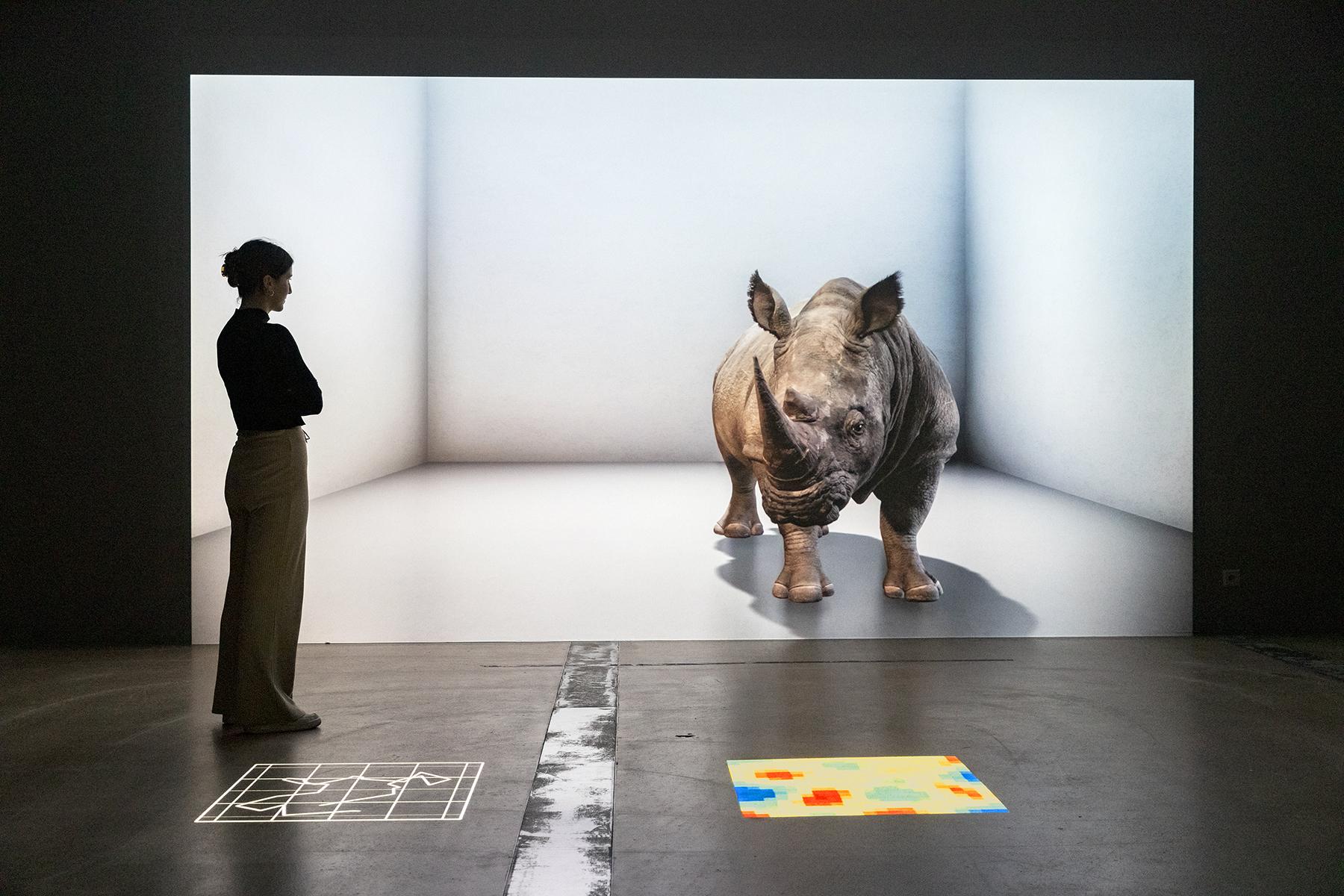

Current installation: The Substitute

Artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s video installation was inspired by the death of the last male northern white rhinoceros – and scientists' plans to bring this extinct species “back to life” using biotechnology. A life-size projection shows the massive creature roaming in a virtual world – alternating between a strikingly lifelike and a pixelated form. These repeated transformations remind us that the apparently real rhinoceros is entirely artificial, confronting us with the question whether man-made objects can ever be a substitute for real life forms. Please note that this exhibition will open on March 1, 2022.

Apocalypse TV

Apocalypse TV goes with the exhibition «Apocalypse – End Without End». The online channel lights up the diversity of the topic in episodes on a regular basis. The reporter Lukas Landolt meets people who have something to say. And he traces our relation to downfall, with all the fears and all the lust that the apocalypse also provokes.

Voices of the exhibition's makers

"The end of the world is something that affects everyone. Any exhibition dedicated to the topic is going to move constantly between "high" and "low", switching easily between cultural and scientific reflection and more mundane, popular perceptions. You get to embrace the trash while remaining deadly serious. It's the best thing that can happen to you as an exhibition designer - the Apocalypse provides a licence for role plays of the subtlest and not so subtle kind."

"Contributions from around twenty different artists bring a wide range of perspectives into the exhibition. Their work comments on, questions, confirms, ironizes or complements the scientific accounts presented, and this establishes an additional level of discourse which runs throughout the rooms right up until the open end. The variety and internationality of the artistic positions here is proof of the existential draw of the topic."

"Apocalypse: it's a word which sounds definitive and final, but the possible ways of approaching it are endless. Our exhibition explores the 'end without end' by compiling a range of different and sometimes contradictory positions. Natural threats are juxtaposed with manmade dangers, hard facts with daring speculations, fear set against hope. What does the audience get from it? An interdisciplinary, apocalyptic rollercoaster in seven rooms."

"What kind of architecture does the Apocalypse need? It's all about lending a strong form to uncontrollable forces which defy any attempt to tame them. At the start of the exhibition we go up high, towards the sun. From then on we're captive, in rooms whose layout is not random but governed by a unique and idiosyncratic logic. Lured by the aesthetic of reduction and driven by the content we find our way to the inevitable end - of the exhibition."

"This exhibition is an important milestone in the implementation of our new strategy: to present the natural sciences in a way that integrates cultural science, art and society. We believe that our innovative exhibition concepts will turn this Bern-based museum into the leading natural history museum in Switzerland, as well as strengthening its international reputation and standing. By taking a multispectral approach, we hope to appeal to a broader audience - to speak to a wide range of visitors with accordingly varied interests. Our aim is to confront exhibition-goers with topics of acute relevance, approached through the lens of their own experience, thus opening as many doors as possible to a deep and inspiring understanding of the issues in question and of nature as a whole."

"Why is a natural history museum putting on an exhibition about the end of the world? Because it's a fantastic story that affects everyone - everyone has a stake in it and it's always relevant, whatever the climate of the current age. On top of that, the Apocalypse is about as interdisciplinary as it gets, a topic which brilliantly combines elements of science and art. The exhibition explores it fearlessly but without taking away the magic - when all's said and done, the end of the world remains a mystery."

"Asteroid hits and nearby supernovae are scenarios which are possible, but not likely to occur. It's still important that we inform ourselves about the dangers, though, because this makes us aware of the fragility of our existence. Our options for preventing mega-catastrophes are extremely limited, so it seems to me even more important to focus on our treatment of the planet and on protecting at-risk populations in volcanic regions and earthquake zones."

Beni Bischof

*1976 in St. Gallen, lives and works in St.Gallen and Widnau

Michele Bressan

*1980, lives and works in Bucharest

Jake & Dinos Chapman

*1966 in Cheltenham and 1962 in London, live and work in London

Julian Charrière

*1987 in Morges, lives and works in Berlin

Chiu Chih

* in Taipei, lives and works in London and Shanghai

Gino de Dominicis

1947 in Ancona – 1998 in Rome

Roberto Fassone

* 1986 in Savigliano, lives and works in Florence

Omer Fast

*1972 in Jerusalem, lives and works in Berlin

Andreas Greiner

*1979 in Aachen, lives and works in Berlin

Ingo Günther

*1957 in Bad Eilsen, lives and works in New York

Camille Henrot

*1978 in Paris, lives and works in New York

Markus and Reto Huber *1975 in Münsterlingen, live and work in Zurich

Marc Lee

*1969 in Knutwil, lives and works in Eglisau

Armin Linke

*1966 in Milan, lives and works in Milan and Berlin

Vladimir Nikolić

*1974 in Belgrade, lives and works there

Katie Paterson

*1981 in Glasgow, lives and works in Berlin

Elodie Pong

*1966 in Boston, lives and works in Zurich

Batoul Shimi

*1974 in Asilah, lives and works in Tétouan

Roman Signer

*1938 in Appenzell, lives and works in St. Gallen

Kasper Sonne

*1974 in Copenhagen, lives and works in New York

Superflex

founded in 1993 by Bjørnstjerne Reuter Christiansen (*1969), Jakob Fenger (*1968), Rasmus Nielsen (*1969), the artists live and work in Copenhagen